World Geostrategic Insights interview with Paul Goncharoff on the real impact of Western sanctions on Russia, the resilience of the Russian economy, its current state, and the medium- and long-term prospects.

Native to Manhattan, Paul Goncharoff has lived and worked in Asia, the MENA region, Europe and, since the late 1990s, based full-time in Russia. With his company Goncharoff LLC, he is dedicated to business management, development, integration, and consulting in relation to Russia/FSU markets, working with Russian and non-Russian companies wishing to operate in the Russian Federation and outside Russia, managing multicultural business, operations, and personnel in urban, regional, and remote areas of Russia/FSU.

Q1 – Russia’s economy has emerged relatively unscathed from two years of war, which seemed hard to predict given tough Western sanctions and tensions due to the war with Ukraine. So what was the real impact of the sanctions?

A1 – Context matters when speaking about Russia, Western sanctions, and the Ukraine conflict. Western sanctions against Russia began in 2014 when Crimea was “annexed” by Russia, through a majority referendum in Crimea and a popular vote.

On March 17, 2014, President Obama issued Executive Order 13661 under the national emergency concerning Crimea essentially freezing political, economic, and trade relations with the peninsula. The EU joined in by banning imports of goods originating in Crimea or Sevastopol, unless they have Ukrainian, not Russian certificates; and by prohibiting investments in Crimea: Europeans and EU-based companies could no longer buy or sell real estate or entities in Crimea, finance Crimean companies, or supply related services.

Meanwhile, a Ukrainian civil war proceeded to gather steam in the Donbass, costing the lives of more than 14,000 Ukrainian citizens living in the Donbass, who culturally, historically, religiously, and linguistically identify themselves as Russian, and have opposed the new Western supported exclusionary policies of the Kiev regime.

The sanctions response by the Western governments in 2014, and regularly tightened in the following years, allowed Russia, which clearly saw the writing on the wall, to prepare itself for increased economic isolation by Western sanctions.

By February 2022, after numerous additional sanctions were already placed on Russia by the West, the Russian military entered the Donbass, joining with, and attempting to protect, the residents of the Donbass in their fight against the Kiev government and its military forces. By the same token, the population of the Donbass, in both regions of the LNR and DNR, chose to hold a referendum and conduct a vote to legally become part of the Russian Federation, which is what happened.

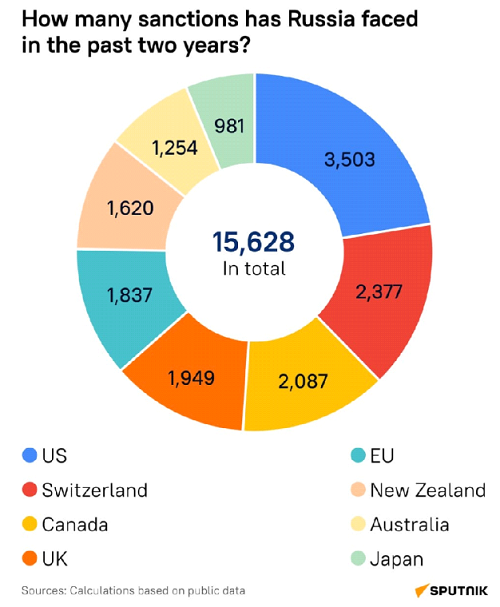

In summary, the West and the aligned countries have seen fit to impose on Russia the largest number of economic and trade sanctions ever imposed on a country in history, for the benefit of whom?

The real impact of these numerous restrictions has been manifold. For Russia, they served to notify the commercial and manufacturing sectors that they had to quickly gear up internally, as well as together with what is now called “friendly” countries by substituting both essential and non-essential products and technologies that before sanctions were freely obtained from the now “unfriendly” countries in the West that sanctioned free direct access to their markets.

In short, sanctions enabled Russia to strongly develop its industries under the flag of “import substitution” ending reliance on the West. In addition, they served to accelerate de-dollarization, the growth of BRICS+, and the many additional countries that align with a common belief in multipolarity and the sovereign rights of nations.

In the West, sanctions have encouraged the media to indulge in mass-misinformation about the impact of these measures. This has been additionally fed by either woefully inadequate or deliberately dubious market intelligence both within and beyond their own borders. Instead of the destruction of the ruble, the currency strengthened.

Instead of Russia’s economy collapsing, it grew at higher GDP terms than any Western nation last year, while the IMF has predicted it to do the same in 2024. Europe, having cut off cheap Russian gas, has done so at the expense of its own global manufacturing competitiveness. It has now become reliant and a customer of the United States. That means it has just one main energy partner now and is becoming Washington-dependent with the United States that will always place its interests first. The implications of this are only now being thought through and then again only in limited circles.

Q2 – How has Russia survived Western sanctions?

A2 – In simple terms, it is due to an intense effort to produce needed goods inside Russia, with friendly countries, and with its massive “Pivot to the East” which essentially shifted almost all trade and economic activity to the East and Global South of the world. Throughout 2022/2023 Russian trade data suggests that Russia effectively replaced the entire European bilateral trade and supply chain and most products by the end of 2022. This was accomplished by boosting internal production and consumption, developing trade ties with all of Asia, engaging in parallel imports, and boosting trade with other global partners elsewhere. Russia has removed its previous reliance upon European products and is obtaining them either domestically or from other global markets.

Q3 – What is the resilience of the Russian economy based on? How would you describe the current state of the Russian economy?

A3 – Sanctions have had an undeniably harsh effect on Russia, especially at their beginning when Russians had to suddenly shift their thinking and actions to apply imaginative solutions at high gear.

As the years passed, many if not most Russians saw the sanctions as a personal challenge that supported independence from imposed restrictions, the sovereign right to succeed despite all headwinds set against them, and the pride that comes with these myriad successes. It has also served to stoke up real grassroots national spirit, which is not the brashly advertised sort.

As one acquaintance of mine, a manufacturer in Russia’s heartland of Ekaterinburg said “If it wasn’t so very serious an issue to remove the bad effects of Western-imposed restrictions, I could say I am enjoying this game of geo-chess, and as you can see by our business results, I fully intend to win it”. This sort of sentiment I have found widely shared among the businessmen of Russia, and those doing business with Russia.

As a result, Russian consumer tastes are also changing. Rather than being based on the West, a larger variety of new and new-to-Russia brands are entering the market. The domestically owned Tasty Dot burgers have replaced all 900 McDonald’s outlets and increased their sales beyond that achieved by the original owners.

Other aspects of life, such as Indian and Chinese restaurants opening, consumer outlets such as Zara being renamed as Maag but retaining the same supply chains, Asian cosmetic brands replacing French, and an appreciation for the overall quality of Chinese automotive products. Two years ago, Chinese cars had a 5% share of the Russian domestic auto market. Now it’s at 45%. There are hundreds of such examples.

Q4 – Is there currently a so-called war economy in Russia?

A4 – There undoubtedly is a high demand for war-related products, especially disposables such as ammunition, and not only in Russia, ask any arms manufacturer in the West as well, they are not complaining about any lack of business, just glance at their share prices. Cash registers ring with each expended round.

In terms of Russia, the economy during times of military conflict tends to focus on independent self-sufficiency, and interdependency among and between sectors – from industrial and scientific R&D, microchips, chemicals, electronic manufacturing, metals, machining, transport, agriculture, and in Russia’s case alternatives to the Western financial systems of settlement.

I wouldn’t necessarily call it a war economy, but rather an economy that must grow in times of sanctions. That tends to prioritize activity and win hearts and minds to join in a concentrated national effort. What we are seeing is more the effect of a resurgent Russia. Growth and demand are both vibrant. If the Ukraine situation didn’t exist, Western investors would be piling into Russia right now. Asian ones already are. The actual growth driver in the Russian economy is Asia, not the Ukraine conflict.

Q5 – What are the medium- and long-term prospects?

A5 – The medium and long-term prospects for Russia in my view are largely positive as the world has and still is realigning tectonically. Russia is a key part in the new power shift which brings together many nations within the umbrella of BRICS+++, SCO, AfCFTA, EEAU, GAFTA, EEU, and others sharing similar visions of multilateral empowerment and growth, independent of the historically established Western model mostly, but not entirely represented by the G7. This enables Russia, as it does other participating countries, to continue to develop and grow unfettered trade, deepening economic relations, as well as avoiding the political pitfalls and financial risks attached to relations with unipolar Western interests.

Q6 – Some members of the European Union (EU) and NATO seem to have increased their exports to Russia despite the conflict in Ukraine. How do you explain this?

A6 – The nascent attempts at the rebirth of free trade. After all is said and done, after the posturing, politicization, threats, fear-mongering, and loud speeches that bang like drums daily from legacy media out of Brussels and Washington – diplomacy is starting to reassert itself in the guise of its historic origins which are not political. The origins of diplomacy lie within active trade.

In very basic terms, this conflict has illustrated that Russia needs Europe rather less than Europe needs Russia. In purely geographic terms, for every 1 km of border Russia has with the EU, it has 3.5km to the East.

Without the pendulum of political opinion swinging at least partially back to conflict resolution and at least a partial resumption of energy supplies from Russia, it is hard to make much of an economic growth case for Europe. The United States will be fine, and Russia is already adapting. It is Europe that has the more significant problems.

Paul Goncharoff – Principal of Goncharoff LLC, Moscow

Image Source: discovermoscow.com