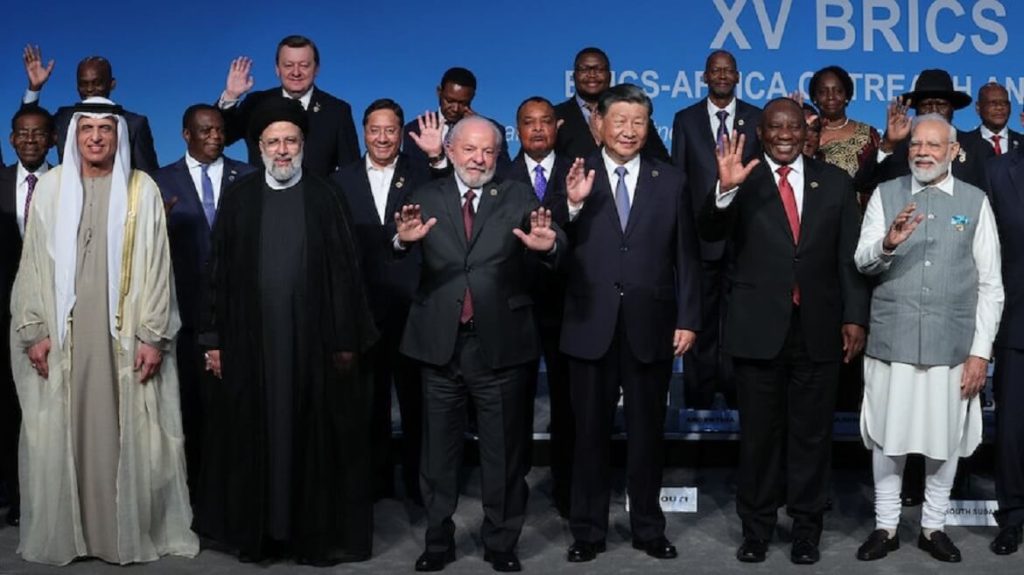

The enlargement of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) planned by the Johannesburg summit represents a historic milestone for this organization and for global balances. As of Jan. 1, 2024, the group will already welcome six new members (Ethiopia, Egypt, Argentina, Iran and Saudi Arabia), while the list of candidate countries for BRICS membership is lengthening.

Bringing together the countries of the Global South to establish a new multipolar world order to end the hegemony of Northern countries and the supremacy of the dollar, this seems to be the overall goal of the group.

To explore the status and role of the BRICS in global governance, and aspects related to possible competition and cooperation with the G7 countries, a major study conference was held on Nov. 30 at the faculty of La Sapienza University in Rome, promoted by the Foundation for International and Geopolitical Studies. Speakers at the conference were: Antonella Polimeni, Magnificent Rector of Rome’s La Sapienza University; Oliviero Diliberto, Dean of the Faculty of Law at La Sapienza University; Paolo Savona, President of Consob; Lamberto Dini, former Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs; Giancarlo Elia Valori, President of the Foundation for International and Geopolitical Studies.

Speakers’ presentations at the conference are summarized here.

Antonella Polimeni, Magnificent Rector of Rome’s La Sapienza University

Welcome and introductory address – A kind of macroscopic disorder, an absence of governance of the world order, characterizes the current international context, with the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war and the conflict in the Middle East being further catalysts of such a disruption. In this climate of uncertainty, of identity crisis, appears the scenario of a new multilateralism and enhanced protagonism of the developing countries identified in the acronym BRICS. Indeed, Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (founding countries of the BRICS) with their geographic extent, population, natural wealth, and energy resources, represent a formidable world-level agglomeration.

On January 1, 2024, Saudi Arabia, Argentina, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia and Iran will join this bloc. The BRICS will thus account for 36 percent of the world’s GDP and 47 percent of the population of the entire planet. And this first phase of enlargement will be followed by another wave of further expansion.

The BRICS include countries that are very different from each other, in terms of history, culture, political institutions, economy and religion, but united by the desire to count more on the world stage, particularly with regard to the West, symbolically represented by the G7. Global scenarios are therefore changing, and Europe will certainly have to equip itself to face and interact with these powerful new realities. It is therefore crucial to understand the causes of the phenomena we are facing and to propose solutions.

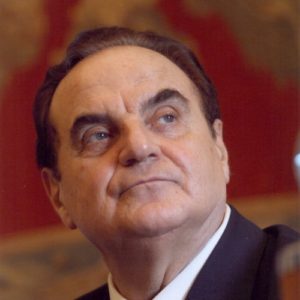

Oliviero Diliberto, Dean of the Faculty of Law at La Sapienza University

In today’s international disorder I see no hypothesis of a new order. Wars, massacres, explosion of national and ethnic selfishness, religious fundamentalism, clashes between powers, border closures and tariffs are the consequence of the disorder not the cause.

In 1945, the victors of World War II, while profoundly different from each other, established a new order that worked because it was plural. Indeed, the very rigid bipolar balance at the end of World War II, while certainly limiting national sovereignty within the two blocs, ensured a long period of peace, albeit with very violent opposition between the two blocs.

This period of peace, which lasted until 1989, represents a momentous watershed. The United States, winner of the Cold War, did not even try to build a new shared order. In fact, the end of the Cold War opened a new phase, not the end of ideology as has been written, but the dominance of a single ideology, the neoliberal ideology. Francis Fukuyama’s idea prevailed that after 1989 there would be a new world forever pacified, the end of history, under the aegis of the values of the West. However, another influential view, that of Samuel Huntington, that victory over Soviet communism would not end the conflict, but would turn it no longer into a conflict between ideologies, but into a conflict between civilizations, between cultures, between religions, in a word into a conflict between identities, was not taken into account.

Huntington’s prediction punctually came true And in fact, after ’89, instead of an end to the conflict, a season of conflict and overall instability opened: first the atrocious and terrible war in Yugoslavia in the early 1990s with massacres, ethnic rape and nefariousness of all kinds. Then the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and other conflicts, such as in Syria and Yemen, in Libya where there is no longer a state and a tribal war is going on whose outcome we do not see. Up to the current conflict in Ukraine and the so-called asymmetric war between Israel and Hamas.

Equally complex is the situation of economic and trade relations. The tariff war between the United States and China has slowed the entire economic growth of the planet. This contention is not being addressed within the WTO, that is, the supranational institution that should govern it, but within a purely bilateral confrontation between the two powers. The Paris climate agreement is under attack. The dramatic and growing problem of migrants in the world cannot find an international agreement that overcomes national selfishness. The crisis of international institutions.

The decision-making mechanisms of the United Nations are tied to the balances present at the end of World War II, which are simply no longer there. Day after day we register the impotence of the United Nations, and equally evident is the crisis of the European Union with its substantial impotence to assume any role in the global chessboard. Similar signs of crisis can be seen in the Arab League itself torn apart by internal divisions and in NAFTA, which is in trouble due to the emergence of the different interests of its individual components. NATO has been perceived as a problem by the U.S. establishment itself.

There is political-economic opposition to the unipolar world of the 1990s, poor countries versus rich countries, intertwined with ethnic-cultural and religious opposition. A report by the European Council on Foreign relations reveals a collapse of the West in the eyes of emerging countries and how global dynamics are changing. In fact, 40 percent of non-Europeans believe that the power of the European Union will crumble in the next two decades, and emerging countries are proving increasingly open to Chinese intervention in their economies.

It is in this context that the emergence, development and enlargement of the BRICS should be analyzed. As early as Jan. 1, 2024, they will account for 37 percent of the world’s GDP, 47 percent of the planet’s entire population, 41 percent of the world’s oil production, and be leaders in the production of zinc, copper, lithium and rare metals. On August 23, at the last BRICS summit in Johannesburg, the concluding official communiqué emphasized the importance of encouraging the use of local currencies, thus no longer the dollar, in international commercial financial transactions between the BRICS and their trading partners.

The South African president portrayed the BRICS as a champion of the needs and concerns of the peoples of the Global South and of inclusive multilateralism. Other BRICS leaders, including the Chinese president, have also said that BRICS will strengthen the confidence of many emerging and developing countries in a new multipolar world order.

In the BRICS countries, with the exception perhaps of the Russians, the anti-Western narrative is not prevalent. They are demanding to count more and a new multipolar world balance. Ultimately, a new world order that is not there now, but only such a renewed order could once again ensure decades of prosperity and peace and a return to the breaking down of trade barriers with international free markets-in a word, a new order to spread prosperity globally.

Paolo Savona, President of Consob

In examining the topic of BRICS and the new world order, we must be aware of the concepts of cooperative model and competitive model in geopolitical relations. Globalization is the ultimate economic expression of competition with geopolitical cooperation. Here the two models may converge, enhancing economic and social progress; and they compete only if politics wills it, not because of their inherent nature.

Competition is seen as an “unfair” way to manage scarce resources, because the best (which is sometimes the strongest) wins, and so cooperation is needed, which is meant to help the weaker (or less strong). Competition and cooperation are two sides of the same coin coined for individuals, businesses, and states. After two tragic world wars and a bitter struggle for supremacy over how to organize a society, we arrived in the latter part of the 20th century at a model world order with cooperative and competitive features in close harmony with each other. The key moments in this selective historical process were the Bretton Woods agreements of 1944, the Sino-US Shanghai Agreement of 1972, the dissolution of the USSR in 1992, and the birth of the WTO in 1995, which China joined in 2001.

These and other international agreements have created a geopolitical-economic order that has never completely dismantled protective barriers to trade, nor stopped local war conflicts, but has curbed the outbreak of wider conflicts and allowed global trade to expand, benefiting the real growth of most countries in the world. Such a World Order has allowed world trade to double since its inception, dragging the domestic growth of countries in proportion to their ability to participate in global trade, as indicated by their respective terms of trade.

The above model is being challenged today by events related to the unresolved confrontation between the U.S.-Rest Of the World bipolarity and the U.S.-China-Rest of the World multipolarity (Russia, India, and some 50 other countries proposing a competition-cooperation bloc model, as intended to be the BRICS that has grown from 5 to 11 and with an expected enlargement to 51.

According to documented analyses, a competition-cooperation bloc would provide limited performance compared to the global solution. Worse would be if the trend toward a protectionist model between countries or between politically organized areas crystallized, as evidenced by the application of two thousand new tariffs to international trade, because the damage to real growth and global civil coexistence would be irreparable. The risk would be even greater if protectionism without political cooperation fuels new and worse war conflicts; it is no coincidence that there is already authoritative talk of the beginning of a “fratricidal” world war.

Globalization, with all its faults, has lifted about one billion of the Planet’s inhabitants out of poverty, raised, albeit with significant differences, the level of well-being of another six billion, and created spaces of new life for another billion of the Planet’s inhabitants. Infrastructure investment remains the vehicle for national growth and international cooperation. It is non-cooperation that creates less welfare and more poverty. The cooperative model has no alternative for the welfare of the Planet’s population, while the non-cooperative model is the path to disaster.

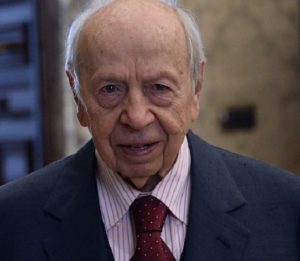

Lamberto Dini, former Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs

As Henry Kissinger wrote a few years ago, after the World War, the quest for a world order has long been inspired almost exclusively by the founding principles of Western societies. The United States, relying on its economic supremacy, identified its action with the promotion of the ideals of freedom and democracy, attributing to these forces the capacity to create prosperity and ensure a just and lasting peace.

Indeed, the spread of democracy and individual rights has been the goal of the existing international order. However, in the past decade, as the West’s tensions with Russia and China have escalated, the concept of world order, which has ruled international relations so far, has entered an irreversible crisis. What have been the causes? Over the past 30 years, with the free exchange of goods, capital and technology and economic globalization, there has been an unprecedented growth in the income and welfare of so many countries on the planet.

In relative terms, the weight of the U.S. economy has declined and that of the Chinese economy has grown the most, surpassing that of the United States in various indicators. The weight of the economy of the five countries in the so-called BRICS bloc, that is, Brazil, India, Russia, China and South Africa, has exceeded the weight of the economy of the G7, that is, the world’s most industrialized countries: the United States, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and Japan. Within this framework, the BRICS countries foreshadow the construction of a new world order and to counter the dominant role of the dollar in international trade transactions.

It is indisputable that the United States, the world’s largest democracy, remains the richest and most advanced country in the world in terms of capital, per capita income and scientific and technological innovation. But, on the other hand, China’s autocratic and authoritarian system has not prevented it from achieving decades of extraordinary economic growth, while also revealing the fallacy of the belief expressed by U.S. leaders that economic development would facilitate the emergence of a more open and liberal system in China.

On the contrary, in recent years and to date, the Chinese state, with an ideological policy that combats diversity and insists on convergence and uniformity, has become more centralized and stronger. Xi Jinping wants a country that is less open internally and more assertive externally. Moreover, China’s leadership and the country’s most influential academics argue that China, which has now become a major economic power comparable to the United States, must have a new major leading role in international relations, arguing that a world that has become multipolar requires a new world order that does not coincide with the one dominated by the United States and the dollar.

For China and Russia, this is not only a question of power, but also a battle of ideas: the Western tradition, which promotes individual freedoms and human rights on a universal level, is being pitted against that of the great autocratic countries, according to which different cultural traditions and civilizations must be allowed to develop differently. The new world order they advocate would thus be based on distinct spheres of influence, characterized by particular internal structures and forms of government.

This approach inevitably clashes with the policy followed so far by the United States. In fact, according to Russia and China, the US imposes the ideas of democracy, individual freedoms and human rights on other countries even through military interventions. China, which is now the world’s largest exporting producer of manufactured goods, uses its trade power, combined with vast infrastructure investments, to expand its influence in the world. American economists admit that China’s grip on world markets has become such that it cannot be stopped. With a population nearly four times that of the United States, China has become the great geopolitical and strategic rival of the United States.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that China poses the most powerful and determined threat to the U.S.-led world order, because China not only intends to change the international order, but also has the power to do so. Therefore, the United States is seeking to strengthen cooperation with other countries to meet this challenge. To curb the growth of the Chinese economy, the United States, contravening the rules enshrined in the World Trade Organization, is resorting to intensified protectionist measures, introducing restrictions and controls to block China’s, and also Russia’s, access to American technologies.

The U.S. measures have been the main factor in slowing the growth of China’s economy, which will fall to 3 percent in 2022, growth that is too low to meet the expectations of increased employment and welfare of a large urbanized population. Indeed, Chinese exports to the United States have declined. However, exports to other countries have increased, such that today China’s exports to Third World countries exceed those to the United States, European Union and Japan combined. Overall, China continues to run a strong trade surplus with the rest of the world; its international gold and currency reserves exceed the equivalent of $3.2 trillion. Incidentally, it should be noted that this year China will be the world’s largest exporter of electric vehicles, a record that will not be easy to break.

The economic and financial sanctions imposed on Russia after the invasion of Ukraine had a major impact on the Russian economy, which went into recession and the collapse of exports was followed by a sharp depreciation of the ruble. These sanctions, however, created additional costs for European countries that depend heavily on gas and oil imports from Russia, and triggered inflationary processes in these countries, with significant losses in purchasing power. And, as a side effect, the sanctions have reinvigorated and welded Russia’s already strong economic and political ties with China. Preventing Russia from using the dollar in international payments has led to the development of bilateral clearing agreements with third countries and arrangements to pay for trade transactions in currencies other than the dollar. They have also encouraged a rush to buy gold by central banks of various countries, including China and Russia, to reduce the percentage of dollars held in their international reserves.

Sanctions against Russia have not been welcomed not only by China and India but also by most countries in the so-called Greater South, i.e., Asia, Africa and Latin America, that together have the strength to diminish the West’s influence at the United Nations and in other international institutions. The liberal democracies of the West are now pitted against almost everything else in the world. In the United States the protectionism of the new industrial trade policy is likely to endure, so Europe will soon be forced into a costly retrenchment of trade and investment in its relations with China.

Once market fragmentation gets underway, it is difficult to control it, much less reverse it. Despite the recent meeting between Biden and Jin Xiping in San Francisco, the main reasons for the China-U.S. rivalry remain unchanged, as well as the resulting global tensions. As a result, for a not-too-short time, there will be lower production efficiency and higher costs, lower growth in the world economy and thus lower welfare.

The antagonism of Russia, China, the BRICS and other emerging countries toward the dominant role of the United States is likely to persist throughout the decade.The existing world order is severely challenged, but a new, more shared order is not yet emerging.

Giancarlo Elia Valori, Manager, Economist, Professor Emeritus of Peking University, President of the Foundation for International and Geopolitical Studies, Presidente of International World Group

Concluding remarks – BRICS aims to reduce the consequences of the global economic crisis, improve people’s quality of life, and support a gradual transition to the most advanced technologies in the broadest possible sectors. The entire group of Bric countries is turning into a large community having a very important role, as evidenced by the growing number of new member countries and applications for membership.

The BRICS, unites the efforts of countries seeking to overcome imperialist economic hegemony, strengthen economic integration, and above all develop economic activities. The BRICS has certainly broadened its objectives, devising economic strategies also aimed at changing the architecture of the international financial system, in order to reduce the role played by the dollar, consolidate the capacity of the member countries, and above all counter capital flight triggered both by economic processes, the ebb of foreign investment, and the end of U.S. monetary stimulus.

Within this framework, the figure of Xi Jinping clearly emerges. In fact, as early as February 2017, the President of the Republic of China, identified as his main task the promotion of BRICS to attract a large number of non-participating countries to the organization.

Global dynamics are changing. As already highlighted by pof. Oliviero Diliberto, a report by the European Council on Foreign Relations reveals the Collapse of the West in the eyes of emerging countries. Forty percent of non-Europeans believe that the power of the European Union will crumble in the next two decades. Instead, emerging countries are increasingly open to Chinese participation in their economies.

The Shanghai-based New Development Bank (NDB), the multilateral development bank established by the BRICS, with $100 billion in capital, finances projects to create, expand and improve infrastructure in member states.

Experts consider the People’s Republic of China as well as India, the world leaders in the supply of manufactured goods, and the potential frontrunners in the delivery of services, while Russia and Brazil are expected to take on the role of the world’s main suppliers of raw materials. It is assumed that the economic unification of the BRICS countries does not guarantee, but nevertheless offers the possibility of the emergence of a strong bloc of viable authority.

I want to reiterate the essence and value of President Xi Jinping’s message at the opening of the UN Assembly, focused on peace, dialogue, multilateralism, and cooperation. Above all, and of paramount importance, President Xi Jinping stressed that China will remain committed to upholding the central role of the United Nations on international issues.

I believe that in the world disorder, a world order is coming forward, imposing itself on the world’s attention in an effective and relevant way.

………………………………………………………………..

Curated by: Margherita Chiara Immordino Tedesco – Founder and President of Foundation Placido Immordino and Live Mundi Association.