By David Davidian

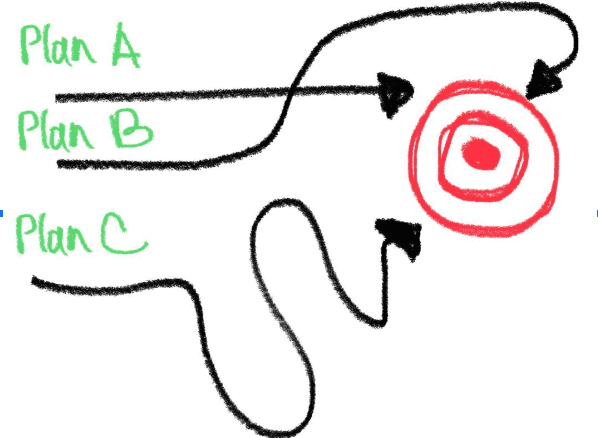

The operational implementation of “Hope for the best, yet plan for the worst” spans the gamut from business startups to grand national strategies and is used in everyday human interaction, from using alternative routes home from work in crowded cities, to birth control.

Regardless of the particular context of application of this principle, few can achieve long-term success when thinking or acting only with a short term view. One could suppose the latter would suffice for goldfish, yet even dogs instinctively bury bones, and squirrels hide nuts, saving them for leaner times when food is not so readily available.

To hope is to want something to happen or be true. While this is part of idle conversation, anything predicated on hope is a wish. No business, security infrastructure, governmental policy, or military can depend on hope as a replacement for planning. Strategic planning involves sacrifices because no national plan can accommodate the complete set of interests of all parties. If a pharmaceutical company wants a new drug approved by a regulatory administration, it may be forced to undergo strict safety procedures. However, the pharmaceutical company may have anticipated such testing and lobbied the regulatory agencies into accepting specific criteria, expressly facilitating easy safety testing to the firm’s advantage. The firm could have hoped, or worse, wished itself luck in gaining the new drug’s acceptance, but rather it took an active initiative. In this case, it was to the financial advantage of everybody concerned to have this new drug approved. However, the lobbying effort could be detrimental to the consumer as fast-track testing cannot replace determining long-term effects, as this is a function of time. Drug and biotech companies have gone bankrupt, as many have faced massive losses due to lawsuit compensation cases or approval rejection. Many didn’t appear to have a plan B or C, or even D. Luck, hope, or arrogance will never replace planning. Nor can adequate planning serve all parochial interests.

The Post-Soviet Space

The latter decades of the Soviet Union — especially the last — nurtured a unique type of corruption. Engaging in non-state-sanctioned profiteering symbolized success against the prevailing Soviet command economy. This fact is significant as the societal glorification of the oligarch emerged. Such profiteering usually involved the theft of state property of some sort, engaging in contraband, etc. Immediate post-Soviet, Russian, Armenian and Georgian officials kept their tradition of rampant corruption, with Azerbaijan approaching the pinnacle of oil-state corruption and one-family rule.

From Moscow’s immediate post-Soviet perspective, Azerbaijan was a relatively ancillary geopolitical outpost. In the post-Soviet chaos, Azerbaijan remained largely ‘out of sight, out of mind’ to Moscow, and theft became a free-for-all during the 1990s. Privatization procedures favored former KGB officials, friends, and relatives of the nouveau-riche and others with private militias. Law enforcement and judicial systems were swayed in the interests of this oligarch class, members of which had positions as members of parliament.

Armenian and Georgian buildings were stripped of marble and artistic figures, and factories that ended up in the hands of former Soviet directors were emptied with their contents sold to Iran and other countries. In Nagorno-Karabakh, railroad tracks were stolen and sold as high-quality steel. The same was done with the trolley system in Tbilisi, Georgia. Transition metal (copper, molybdenum, gold, etc.) mines in Nagorno-Karabakh owned by Armenian oligarchs, were subject to minimal tax, if any, and other privileges not available to those outside their class. Such ‘creative’ thievery was endless, while education, military modernization, the diplomatic corps, and civil society suffered. Becoming wealthy is not a crime unless it comes at the expense of state property, state security, military preparedness, and a general betrayal of the citizens who suffer because of it.

The corruption continued unabated across all successive governments in this post-Soviet era, with the oligarch class writing and amending laws for their benefit. And that corruption and mentality continue today.

In Georgia, Bidzina Ivanishvili, the country’s richest person, effectively runs the show today with a parliament full of oligarchs. In Armenia, the parliament is littered with old-time oligarchs and new ones in the making. In both states, as in most others, there is an official ban on government officials enriching themselves through the privilege of their positions. Yet the corruption continues.

Such explicit conflicts of interest always undermine state security. The interests of oligarchs are never aligned with those of the state and its populace. This situation is especially critical in Armenia. Not a single one of the immediate post-Soviet oligarchs achieved their wealth by being shrewd business people, good negotiators, or hard workers. They betrayed their country and their people, eviscerating the nation by selling its national assets and sovereign security. The result is an existential threat to national security and sovereignty — and perhaps an eventual loss of a sovereign nation. Lebanon came very close to this status.

During the first two decades of Armenian independence, much of Armenia’s infrastructure was sold off to Russian control, with the convenient rationalization that if under Russian jurisdiction, Armenia would be ‘safer.’ This sell-off enriched the owners of those infrastructures while reducing Armenia’s sovereignty. The myopic perception was that it was easier to cash in than to run their own infrastructure.

One might ask those who say the world is ruled by economic determinism to explain the four to five thousand Armenian young men who lost their lives in the 2020 Karabakh War.

Twenty-two years ago, Vladimir Putin gave Russian oligarchs a choice to exit politics or pay the consequences. One result of this separation was Putin’s ability to rejuvenate Russia’s military industry, a decision which has paid handsome benefits in the war with Ukraine today. Why was the outcome in Armenia so completely different from that of Russia?

Armenia

A government that maintains power through corruption and coercion, by definition, doesn’t have the people’s interests as its top priority. While this may define many world governments today, Armenia has a unique mandate to fulfill, especially with more than seventy percent of its borders blockaded by Turkey and Azerbaijan. All post-Soviet Armenian leaders assumed a static regional power structure, with Russia offsetting Turkish neo-Ottoman expansion ad Infinium. As a result, the development of country experts, critical analysts, and independent think tanks was considered extraneous. One is challenged to find documents delineating Armenia’s strategic interest and direction, either by government officials or its diplomatic corps. Armenia maintained the perception, particularly to Azerbaijan, that they were an exceptional military force. This condition was also a self-perception and shattered in the fall of 2020 when Azerbaijan, under the direction of Turkey, initiated a war to capture Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding regions. Armenia’s previous thirty years, void of strategic planning and analysis, were functionally displayed in the loss of Nagorno-Karabakh in the fall of 2020 and the military and diplomatic inability to address the September 2022 Azerbaijani attack and occupation of over forty square kilometers of Armenian sovereign territory. The subsequent Azerbaijani murder of Armenian POWs and the mutilation of female Armenian soldiers were left to world opinion to address — or ignore as it turned out.

Could Armenia have captured Azerbaijani soldiers on Armenian territory in retaliation? They could, but that would have taken planning and a diplomatic corps trained in confronting such events. Worse, it was only in December 2022 that Armenia announced the formation of a Foreign Intelligence Service. The embarrassment of such an announcement is overshadowed by the consequences of never having had such an institution. The Russia-led CSTO never came to Armenia’s aid as Azerbaijani forces entered Armenia. Such agreements and alliances must be constantly evaluated, as nothing is written in stone.

The Armenian government has yet to articulate alternatives to its preferred static world. Rather than plan much of anything that might interfere with the gains of an oligarchy, nothing strategic is planned. It may be cynical to assume, but any strategic planning may be associated with five-year plans of the former Soviet state and conveniently rejected. In any case, Armenia never stated its strategic interests or goals to its population. Its population is left assuming the state’s role was to serve the interests of its oligarchs. Since Armenia’s independence, instilling patriotism in the population was always stifled by the lack of expressed direction of the state. Real patriotism, such as demanding or questioning government accountability, had little utility. This is the default Armenian national ethos.

Further, most ex-Soviet citizens who can’t identify a monetary incentive for expressing basic patriotism view such efforts as trivial or suspicious. Armenia’s overt alienation of its diaspora’s capability, especially in the West, is an outcome of an oligarchy that refused to share Armenia’s future. This oligarchy knows Armenians in the diaspora are far more capable than they are and can compete on a much broader scale. The alienation of the Armenian diaspora serves the interests of both Armenia’s enemies and Armenia’s oligarchs. This policy was planned, as is the penchant for never including the best and brightest within strategic government structures.

As 2023 has come, Armenia is left with few geopolitical options, with no national plans B or C, considering a national plan A was never expressed. Years of mutually discordant transactional decisions do not define long-term strategic planning. What remains is imploring the world to help the remaining Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh who are being blockaded by Azerbaijan. These 120,000 innocent civilians are under threat of forced relocation or much worse. Hope will not save these Armenians – a plan might have.

As previously mentioned by this author, a leading hypothesis for the loss of the 2020 Karabakh War is that it was an engineered defeat. Further evidence for this hypothesis is that much of Armenia at the Nagorno-Karabakh border remains unprotected, and projects to enhance the quality of life at these border towns and villages are being slowly abandoned. Alternatively, Armenia’s current passivity could be the result of having been quietly threatened by Turkey and Azerbaijan if it dared engage in endeavors that enhance its sovereignty. It certainly is plausible, given Armenia’s litany of incompetence, inaction, and corruption. A nation so weakened can’t stand up for itself.

One could ask, “What is the plan?” but will never receive an answer. And who are we to question the motives of a government that claims to serve the interests of the Armenian people without ever defining what those interests are?

Yerevan, Armenia

Author: David Davidian (Lecturer at the American University of Armenia. He has spent over a decade in technical intelligence analysis at major high technology firms. He resides in Yerevan, Armenia).

(The views expressed in this article belong only to the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of World Geostrategic Insights).

![Armenia: Hope for the Best, [No] Plan for the Worst](https://www.wgi.world/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/armenia-challanges-1024x664.jpg)